Trauma-informed schools: Supporting teachers in post-COVID classrooms

By Carin L. Reeve

The question is a part of every discussion right now: “When do you think we will return to school?” That question is quickly followed by the next question: “What do you think schools will look like after all of this?”

The decision to re-open schools is complex: there are many interlinked systems that are essential to educating our kids. In the midst of everything that school leaders must consider, one of the most important discussions must be this: how are we going to support teachers as they return to classrooms?

Teachers are among the most hard-working, caring, and generous people I know. I am definitely biased, as I have been in education for twenty-seven years and I come from a family of educators. I have spent every day during the extended closure listening to teachers and leaders in virtual circles. In these circles, teachers have shared their very real stresses, anxieties, worries, fears, joys, successes, celebrations, and humorous anecdotes about being away from their students, balancing their own work and that of their children, and knowing that this time can never be made up. This pandemic, the social distancing, the virtual schooling, the working from home, the fear of the unknown – these have all impacted teachers on a very deep level. And returning to school buildings alone will not undo that impact.

The idea of taking care of the needs of teachers is not a new one. Neila Connors’ book, If you don’t feed the teachers they eat the students!, took a light-hearted approach to the topic in the early 2000’s, and more recently, there has been a call for greater self-care practices in high-intensity fields like education. But, neither self-care nor principal awareness alone will be enough support for teachers in a post-COVID educational setting.

Our current reality must be treated as a collective trauma.

School leaders must approach post-COVID schooling with an understanding of the impacts of trauma and grief on both the mind and the body. For schools where trauma-informed practices have not been the norm, school leaders will need to educate staff about the very real ways that trauma affects learning and social interaction. Schools that already have a trauma-informed mindset may be more prepared, although it is easier to talk about the impacts of someone else’s trauma than it is to address our own.

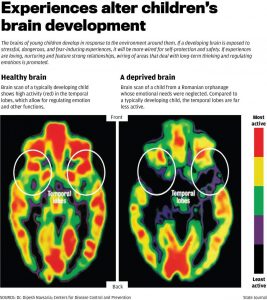

Ongoing research on the impacts of chronic stress and trauma on childhood brain development has identified impacts on both student learning and behavior: students may be more impulsive, less able to pay attention, less able to manage emotions, and less able to make connections. They may have difficulty with memory, with organization, and with any kind of goals or planning due to the parts of the brain that are impacted by chronic stress and trauma. In brain scans taken by the CDC, it is clear that the parts of the brain that deal with those skills are not even active.

While adults are more likely to have coping skills for chronic stress and trauma, not all of those coping skills are healthy. The additional pressure of supporting children who have experienced chronic stress and trauma can trigger adults.

Knowing the impact that chronic stress and trauma has on both children and adults, it is important for schools to be proactive. We have been away from the structure of a school setting for months. There are both adults and children who have been struggling with anxiety, isolation, depression, food insecurity, housing insecurity, financial concerns, balancing work and family, concern for others, and stress about the economic impact of the pandemic. School leaders who understand how these experiences will impact the school community can plan for the return to classrooms.

What we can’t do is pretend that it’s not a real thing and try to squeeze back into the pre-COVID method of schooling.

Many things that used to be “normal” will no longer be normal. And in many ways that is okay. The research around chronic stress and trauma indicates that we can make a difference with supports, services, and strong relationships. School leaders play an important part in supporting teachers as we return to school.

Here are some important things for school leaders to consider:

- Allow time just for processing – not just once, but regularly. Everyone is returning to school with a different personal experience, even within this shared experience. It is important for school leaders to build in opportunities for teachers to talk and process regularly. Using restorative circles as a part of a regular structure for teachers is a way to both model an effective practice and to process feelings about doing school after the extended closure.

- Strengthen personal relationships and lean in to those personal connections. It really is always about relationships. School leaders can remember to listen more, slow down, and breathe. Hearing messages of support and solidarity such as, “I hear you. I feel it, too.” can make all the difference to a teacher.

- Consider school-wide skill building. There are coping skills that can help with the process of rebuilding after trauma. Mindfulness, meditation, and restorative circles are just a few of the strategies that can be built into classroom cultures to support both students and teachers. De-escalation strategies, both for teachers to use in classrooms and for students to use when they are feeling agitated or out of control, are as important to learn as reading and math.

- Remember that clear is kind. One theme has been clear in the virtual circles we have facilitated during the extended closure: teachers have been looking for leadership, and in the absence of leadership, anxiety flourishes and rumors rule. Be clear about what you need from teachers and ask them what they need from you. Building trust in relationships comes from honest communication and responsible follow through.

- Understand that it takes time to move through trauma. There is no set amount of time for dealing with grief, loss, or trauma. Be patient and understanding – even if it feels like you are taking two steps forward and three steps back. As with students, adults will need to feel supported as they move toward a new normal.

As school leaders map out ways to support teachers who are returning to post-COVID classrooms, there is hope and opportunity. While educators should consult with mental health professionals for serious issues like anxiety, depression, agoraphobia, domestic violence, or alcoholism, school leaders can be proactive in ensuring that teachers are supported in our post-COVID classrooms.

Carin L. Reeve is the Director of School Improvement at Peaceful Schools in Syracuse, NY. She has 27 years in education committed to improving outcomes for students and developing excellence in teachers. Reeve spent ten years in school leadership, including four years as a successful turnaround principal. As a part of the team at Peaceful Schools, Reeve shares her expertise with schools, districts, and leaders who are looking to build systems of social, emotional, and academic support for children.